Websocket Client/Server

With Json as Sub-Protocol

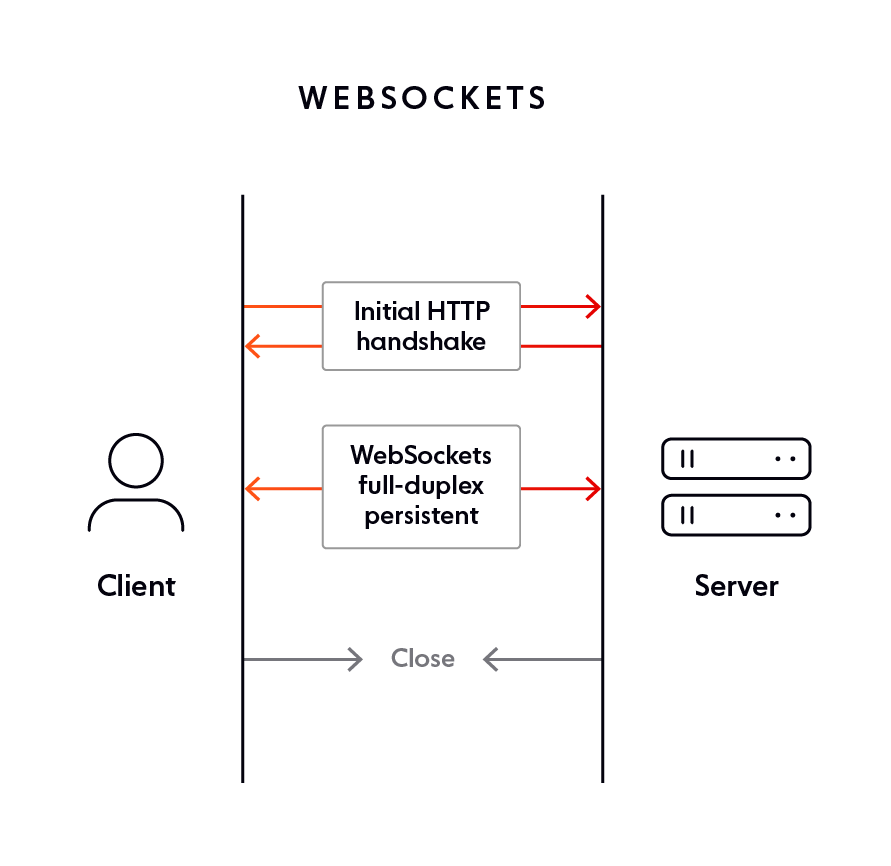

So what are WebSockets anyway?

In a nutshell, WebSockets are a thin transport layer built on top of a device’s TCP/IP stack. The intent is to provide what is essentially an as-close-to-raw-as-possible TCP communication layer to web application developers while adding a few abstractions to eliminate certain friction that would otherwise exist concerning the way the web works.

They also cater to the fact that the web has additional security considerations that must be taken into account to protect both consumers and service providers.

How does WebSocket authentication and authorization work?

WebSockets is a thin layer built on top of TCP/IP, so anything beyond the basic handshake and specification for message framing is really something that needs to be handled either on a per-application or per-library basis. Quoting the RFC:

"This protocol doesn’t prescribe any particular way that servers can authenticate clients during the WebSocket handshake. The WebSocket server can use any client authentication mechanism available to a generic HTTP server, such as cookies, HTTP authentication, or TLS authentication".

In a nutshell, use the HTTP-based authentication methods you’d use anyway, or use a subprotocol such as MQTT or WAMP, both of which offer approaches for WebSocket authentication and authorization.

WebSockets and HTTP 1.1: Getting the ball rolling

One of the early considerations when defining the WebSocket standard was to ensure that it “plays nicely” with the web.

This meant recognizing that the web is generally addressed using URLs, not IP addresses and port numbers, and that a WebSocket connection should be able to take place with the same initial HTTP 1.1-based handshake used for any other type of web request.

Here’s what happens in a simple HTTP 1.1 GET request. Let’s say there’s an HTML page hosted at http://www.example.com/index.html. Without getting too deep into the HTTP protocol itself, it is enough to know that a request must start with what is referred to as Request-Line, followed by a sequence of key-value pair header lines. Each tells the server something about what to expect in the subsequent request payload that will follow the header data, and what it can expect from the client regarding the kinds of responses it will be able to understand.

The very first token in the request is the HTTP method, which tells the server the type of operation that the client is attempting with respect to the referenced URL. The GET method is used when the client is merely requesting that the server deliver it a copy of the resource that is referenced by the specified URL.

A barebones example of a request header, formatted according to the HTTP RFC, looks like this:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

Having received the request header, the server then formats a response header starting with a Status-Line. That is followed by a set of key-value header pairs that provide the client with complementary information from the server, with respect to the request that the server is responding to.

The “Status-Line” tells the client the HTTP status code (usually 200 if there were no problems) and provides a brief “reason” text description explaining the status code. Key-value header pairs appear next, followed by the actual data that was requested (unless the status code indicated that the request was unable to be fulfilled for some reason).

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 1 Aug 2018 16:03:29 GMT

Content-Length: 291

Content-Type: text/html

(additional headers...)

(response payload continues here...)

Meanwhile, it’s worth remembering that piggybacking on HTTP makes using TLS to provide security pretty straightforward.

So what’s this got to do with WebSockets, you might ask? Let me explain...

Ditching HTTP: WebSockets and re-purposed TCP sockets

When making an HTTP request and receiving a response, the actual two-way network communication involved takes place over an active TCP/IP connection.

As we now know, WebSockets are built on top of the TCP stack as well, which means all we need is a way for the client and the server to jointly agree to hold the TCP connection open and repurpose it for ongoing communication. If they do this, then there is no technical reason why they can’t continue to use the socket to transmit any kind of arbitrary data, as long as they have both agreed as to how the binary data being sent and received should be interpreted.

To begin the process of re-purposing the TCP connection for WebSocket communication, the client can include a set of standard HTTP request headers that were invented specifically for this kind of use case:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

Connection: Upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

The Connection header tells the server that the client would like to negotiate a change in the way the socket is being used. The accompanying value, Upgrade, indicates that the transport protocol currently in use via TCP should change.

Now that the server knows that the client wants to upgrade the protocol currently in use over the active TCP socket, the server knows to look for the corresponding Upgrade header, which will tell it which transport protocol the client wants to use for the remaining lifetime of the connection. As soon as the server sees WebSocket as the value of the Upgrade header, it knows that a WebSocket handshake process has begun.

Note that the handshake process (along with everything else) is outlined in RFC 6455, if you’d like to go into more detail than is covered in this article.